My e-mail this week included a heartwarming surprise from the daughter of an Aliceville resident whose mother met and married one of the American officers in charge of Camp Aliceville during WWII. She wrote as follows:

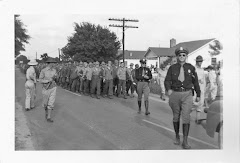

"All of my life I heard stories about 'the camp' and was so delighted to find your book. I have been reading the book to (my elderly mother) and it has brought back so many memories. She vividly remembers the day the first train pulled into the station and the soldiers marched down the street singing--that's one of the stories she told over the years. She always said they looked so bedraggled, but their voices were so strong. I can read a name and she'll remember some little piece of gossip that she hasn't thought about in years! She loved remembering the picnics at Lubbubb Creek, for instance, AND I had always wondered but never knew until your book, what the distinct smell was in the old school sawdust (oiled sawdust). It has been so healing for my mother to relive those years through your lovely book. Thank you so much for giving my mother such a wonderful gift during this last stage of her life."

Friday, October 5, 2007

Tuesday, October 2, 2007

Herbert Jogerst POW Sculptor

A few weeks ago I heard from Michael Rutherford, a historian in Tell City, Indiana who shared a great deal of information about the Indiana Cotton Mills in Cannelton, Indiana, when I was working on my first book, North Across the River. Rutherford had read my new book and sent along an interesting packet of information about a German POW named Herbert Jogerst who was held at Camp Breckenridge in Kentucky.

Jogerst had studied art and sculpture in Strassburg before being drafted in WWII. His military service in the German army took him to Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, and eventually North Africa, where he was captured near Metaches El Bab. In an interview conducted by Gerhard Auer and translated by Sister Ruth Ellen Doane, Jogerst describes his first treatment as a POW. "We were loaded into stockcars....We were collapsing of thirst. There were comrades who were willing to give away their entire fortunes if they could only have a drink. Some soldiers became insane due to thirst."

He describes being transported in this manner through North Africa. "Sometimes we were shot at through the closed wagon (train car) or our guards pushed their bayonettes through the slits in the wagon walls. That was hell. In Casablance we were handed over to the English. Then, for the first time, we were treated as people."

He was sent by ship to Canada and then by train "in Pullman-type cars which were comfortably equipped express train cars" to Kentucky. At Camp Breckenridge, he and 3,000 other POWs kept the streets and barracks clean at a military installation where thousands of American soldiers were being trained.

Jogerst says camp life was monotonous at first. Because he could draw good letters, he became a sign painter and also tried to paint portraits when he had paints. "As the Americans noticed that I was able to paint, my fortune changed," he told the interviewer. One day a guard came to him and said, "The wall in our Mess Hall is so bare. Could you paint something for it?" His fellow prisoners asked him to paint scenery for a theatrical play, which he did in secrecy at night until guards discovered him missing at late hours from his barracks. When these watchmen saw his work, however, they gave him permission to paint without restriction and even commissioned him to paint the altar in the camp chapel.

During his time in Camp Breckenridge, Jogerst was given a barracks to use as a studio and instructed other POWs in calligraphy and figure drawing. When a music pavilion was built by the POWs for their concerts, he built a fountain for it. While others played chess in the evenings, he worked with piles of stone to built the fountain.

One of his most interesting encounters was with the well-known press photographer Alfred Eisenstett (who was Jewish and had worked for the Berliner Illustrierte magazine in Germany before emigrating to the US). Eisenstett was creating a picture report about German POWs for Life Magazine when he visited Camp Breckenridge. When shown the many paintings Jogerst had created, the photographer asked the artist what he planned to do with them. Eisenstett wrote in his article that Jogerst replied, "One day someone will take them away from me."

Among the responses to this article, Life received letters from more than 2,000 readers who wanted to help this German POW preserve his work. As a result, Life placed six overseas trunks at Jogerst's disposal. He was able to send more than 300 of his paintings and carvings home to his mother for safe keeping.

Monks at the Monastery at St. Meinrad (in southern Indiana) http://www.saintmeinrad.edu/ also saw Jogerst's work and took him to the monastery to work as a sculptor until he was sent back to Germany in 1947. When he returned to Germany, Jogerst bought his mother a house and helped her start a grocery business. Then he returned to the US, where he remained until 1962, doing sculpture work at St. Meinrad and also creating statues, baptismal fonts, and altars that can now be found in 28 American states. See also http://www.ctk.org/church-history.htm and http://www.stspeterandpaul.net/parish/history/historical-society/487.php.

Herbert Jogerst died in Germany on April 3, 1993, shortly before a large group of tourists from his hometown of Waghurst came to the US on a trip. Among them was his son Elmar who was able to see much of his father's work for the first time. That work includes an eleven-foot, 6,200 pound statue known to southern Indiana residents as "Christ of the Ohio" because it stands on Fulton Hill at Troy, Indiana, overlooking the Ohio River.

I have in my files the translation of the entire interview with Jogerst, along with excerpts from the History of St. Meinrad ArchAbbey, which contains photos of some of Jogerst's work, and also news clippings from his son's visit. If anyone would like copies, please let me know.

Jogerst had studied art and sculpture in Strassburg before being drafted in WWII. His military service in the German army took him to Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, and eventually North Africa, where he was captured near Metaches El Bab. In an interview conducted by Gerhard Auer and translated by Sister Ruth Ellen Doane, Jogerst describes his first treatment as a POW. "We were loaded into stockcars....We were collapsing of thirst. There were comrades who were willing to give away their entire fortunes if they could only have a drink. Some soldiers became insane due to thirst."

He describes being transported in this manner through North Africa. "Sometimes we were shot at through the closed wagon (train car) or our guards pushed their bayonettes through the slits in the wagon walls. That was hell. In Casablance we were handed over to the English. Then, for the first time, we were treated as people."

He was sent by ship to Canada and then by train "in Pullman-type cars which were comfortably equipped express train cars" to Kentucky. At Camp Breckenridge, he and 3,000 other POWs kept the streets and barracks clean at a military installation where thousands of American soldiers were being trained.

Jogerst says camp life was monotonous at first. Because he could draw good letters, he became a sign painter and also tried to paint portraits when he had paints. "As the Americans noticed that I was able to paint, my fortune changed," he told the interviewer. One day a guard came to him and said, "The wall in our Mess Hall is so bare. Could you paint something for it?" His fellow prisoners asked him to paint scenery for a theatrical play, which he did in secrecy at night until guards discovered him missing at late hours from his barracks. When these watchmen saw his work, however, they gave him permission to paint without restriction and even commissioned him to paint the altar in the camp chapel.

During his time in Camp Breckenridge, Jogerst was given a barracks to use as a studio and instructed other POWs in calligraphy and figure drawing. When a music pavilion was built by the POWs for their concerts, he built a fountain for it. While others played chess in the evenings, he worked with piles of stone to built the fountain.

One of his most interesting encounters was with the well-known press photographer Alfred Eisenstett (who was Jewish and had worked for the Berliner Illustrierte magazine in Germany before emigrating to the US). Eisenstett was creating a picture report about German POWs for Life Magazine when he visited Camp Breckenridge. When shown the many paintings Jogerst had created, the photographer asked the artist what he planned to do with them. Eisenstett wrote in his article that Jogerst replied, "One day someone will take them away from me."

Among the responses to this article, Life received letters from more than 2,000 readers who wanted to help this German POW preserve his work. As a result, Life placed six overseas trunks at Jogerst's disposal. He was able to send more than 300 of his paintings and carvings home to his mother for safe keeping.

Monks at the Monastery at St. Meinrad (in southern Indiana) http://www.saintmeinrad.edu/ also saw Jogerst's work and took him to the monastery to work as a sculptor until he was sent back to Germany in 1947. When he returned to Germany, Jogerst bought his mother a house and helped her start a grocery business. Then he returned to the US, where he remained until 1962, doing sculpture work at St. Meinrad and also creating statues, baptismal fonts, and altars that can now be found in 28 American states. See also http://www.ctk.org/church-history.htm and http://www.stspeterandpaul.net/parish/history/historical-society/487.php.

Herbert Jogerst died in Germany on April 3, 1993, shortly before a large group of tourists from his hometown of Waghurst came to the US on a trip. Among them was his son Elmar who was able to see much of his father's work for the first time. That work includes an eleven-foot, 6,200 pound statue known to southern Indiana residents as "Christ of the Ohio" because it stands on Fulton Hill at Troy, Indiana, overlooking the Ohio River.

I have in my files the translation of the entire interview with Jogerst, along with excerpts from the History of St. Meinrad ArchAbbey, which contains photos of some of Jogerst's work, and also news clippings from his son's visit. If anyone would like copies, please let me know.

Monday, October 1, 2007

German POWs in Owosso, Michigan, too.

I love the seredipity of the writing world and the connections that pop up in unexpected places. I heard this morning from Gary Slaughter who will introduce me at the Southern Festival of Books in Nashville, Tennessee, in two weeks. Gary has written a series of novels set in Michigan during the last year of World War II. The first of these involves two young women who are charged with treason and brought to trial for helping two German POWs escape from a camp. This novel is a fictionalized account of events that actually transpired in Owosso, Michigan, where Gary grew up. For more information on the Owosso camp, see http://www.sdl.lib.mi.us/history/pow_camp.html

Ever since he was a boy, Gary has been fascinated by the subject of the German POWs and has read extensively about them. Like me, he has a small library of books on the subject. I am looking forward to meeting him, reading his novel (Cottonwood Summer--Fletcher House), and comparing notes. http://www.garyslaughter.com/

In his letter this morning, Gary did admit to being a graduate of the University of Michigan, which makes him a Wolverine, and said he understood that that made him a "natural enemy" of any Ohio State graduate who is a Buckeye like me. He did say, though, that he had "forgiven worse in people" and hoped I would do the same for him. Since I have a brother who is a graduate of Michigan State University, I already have practice with this and will certainly do the same.

Ever since he was a boy, Gary has been fascinated by the subject of the German POWs and has read extensively about them. Like me, he has a small library of books on the subject. I am looking forward to meeting him, reading his novel (Cottonwood Summer--Fletcher House), and comparing notes. http://www.garyslaughter.com/

In his letter this morning, Gary did admit to being a graduate of the University of Michigan, which makes him a Wolverine, and said he understood that that made him a "natural enemy" of any Ohio State graduate who is a Buckeye like me. He did say, though, that he had "forgiven worse in people" and hoped I would do the same for him. Since I have a brother who is a graduate of Michigan State University, I already have practice with this and will certainly do the same.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)