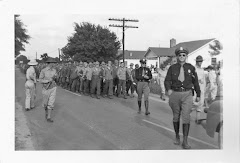

The photo at left shows a Japanese-American soldier guarding German POWs during a peanut harvest in Barbour County, Alabama during WWII. It is part of a wonderful resource--an electronic archive of photos and documents from all eras of Alabama history called Alabama Mosaic.

Photo by Draffus L. Hightower, Clayton Historical Preservation Authority Collection, University of South Alabama Archives. Thousands of similar vintage images are available at USA Archives at www.usouthal.edu/archives/

In my book, Guests Behind the Barbed Wire, I wrote about the Japanese-American guards who took prisoners down to Dothan for the peanut harvest (after they didn't do very well picking cotton), but I had never seen this photo before.

If you'd like to see more wonderful photos of Alabama history, be sure to also check the Alabama Mosaic website. It is at http://www.alabamamosaic.org/.