Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Alabama Mosaic is a wonderful visual resource.

Friday, December 5, 2008

Blount County Program on German POWs

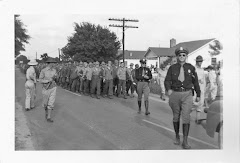

In early November, I made a trip up to Cleveland, Alabama to present a talk and slide show about Guests Behind the Barbed Wire to members of the Blount County chapter of Delta Kappa Gamma (education honorary). After a wonderful catered Thanksgiving-style dinner, the group gathered in the sanctuary of the First Baptist Church.

In early November, I made a trip up to Cleveland, Alabama to present a talk and slide show about Guests Behind the Barbed Wire to members of the Blount County chapter of Delta Kappa Gamma (education honorary). After a wonderful catered Thanksgiving-style dinner, the group gathered in the sanctuary of the First Baptist Church.  I'd also like to thank Jim Kilgore for the wonderful article he wrote about the program for The Blount Countian. It was published in their November 26 issue, and reading it made me so glad that we still have such excellent community newspapers in our state. It is a very well-written story. Often, when I read newspaper accounts of a talk I've given, I hardly recognize what I actually said! Jim's account was accurate and thoughtful, and I believe he'd even read the book.

I'd also like to thank Jim Kilgore for the wonderful article he wrote about the program for The Blount Countian. It was published in their November 26 issue, and reading it made me so glad that we still have such excellent community newspapers in our state. It is a very well-written story. Often, when I read newspaper accounts of a talk I've given, I hardly recognize what I actually said! Jim's account was accurate and thoughtful, and I believe he'd even read the book.Juanita (left) and Marlin Beasley and Ruth Beaumont Cook pose after Cook's book talk at Cleveland's First Baptist Church. The local Beta Chapter of the women's educational sorority Delta Kappa Gamma hosted Cook, who reviewed her latest book, Guests Behind the Barbed Wire.

"For not with swords loud clashing, Nor roll of stirring drums; With deeds of love and mercy, The heavenly kingdom comes," so Ruth Beaumont Cook introduces her book Guests Behind the Barbed Wire. That thought, from Ernest Warburton Shurtleff's hymn "Lead On O King Eternal," echoes throughout Cook's work.

The Ohio native and nearly 40-year Alabama resident offers insight into a fascinating but littleknown segment of Alabama's and the nation's World War II history. Cook spends over 550 pages sharing selected stories of Americans and Germans who lived in wartime Aliceville, Alabama.

As the site of the largest German prisoner of war camp in the United States, Aliceville and its residents came to be touched forever by that experience. The book highlights a few of the over 6,000 men interned in the west Alabama facility, including POWs, prison guards, and other officers who came to Aliceville, some of whom decided to make that their eventual home. Many area residents also found well-paying jobs at the camp. Three of the Germans profiled eventually returned to the United States and became American citizens; another's German obituary proclaimed him an honorary citizen of Alabama; still others, their children and grandchildren have returned to Aliceville to commemorate the up to three year experience.

The ginkgo peace tree weocomes vititors to the Aliceville POW Museum and Cultural Center courtyard. Statues prepared by the POWs lie in the background.

As Cook spoke recently at Cleveland's First Baptist Church, she relayed the story of a daughter of one former POW. Addressing an Alabama reunion celebration, the woman noted that German POWs captured by Russian forces told of eating cockroaches to stay alive. Her father spoke of preparing doughnuts on Sunday afternoons in his Aliceville barrack's kitchen.

The book shares from letters sent to Aliceville residents after the war and of granted requests for supplies forwarded to those who, at times, had taken arms against the givers' homeland. Readers may hardly believe the generosity of a nation to its enemy combatants. The story somehow lifts one to a new appreciation of the nobility of a victorious nation in what the late Studs Terkel called "The [last] Good War."

Cook, in her Cleveland presentation, spoke of the curiosity of Aliceville residents with the first arrival of the POWs. Juanita Prisock Beasley and her husband Marlin were with Cook at the Beta Chapter Delta Kappa Gamma sponsored book talk. Beasley recalled that as a ten year-old she and other residents had disobeyed military orders to remain in their homes on that June 1943 day. Both she and Cook claim the Americans were eager to see these Nazi "supermen," most of whom were veterans of Erwin Rommel's famed Duetsches Afrikakorps. Many of the POWs said the town's people were there to see their horns. Cook contends most saw that day mere boys and felt sympathy for them.

She relates in her book that both the United States and Germany had signed the 1927 Geneva Prisoner of War accord. Under that agreement, POWs were to be treated as the capturing nation's own soldiers. To the United States that meant, among other things, that POWs were to live in barracks as their own soldiers; they were to receive the same food as American soldiers; they were to have recreational opportunities; and they were to be paid for each day of incarceration and additionally for any work they performed. Swiss and Red Cross observers made regular visits to assure conditions met with the accord.

The POWs had leisure time. Many pursued artistic, educational, musical, writing, or sports interests. They created an orchestra, a dance band, a greenhouse, and a newspaper. Money saved through canteen purchases funded most of these leisure activities. Some bargained with their guards or civilian employees for artistic supplies in exchange for drawings or paintings. They decorated their barracks, planted shrubbery, designed gardens, carved outdoor sculptures, built an outdoor orchestra shell, and made of their 120-barrack compounds a home-awayfrom home.

Cook touches on the very different experiences of Aliceville area soldiers captured by the Germans and Japanese and of some who died in that fight. Many Americans know of Japan's harsh treatment of all its prisoners. Neither Japan nor Russia had agreed to the Geneva accord. While Germany had signed, it did not adhere to the accord to the extent of the United States.

The Ohio State graduate contends that Americans had hoped word would reach Germany of their humane treatment of POWs. The thought was that Germany would reciprocate. There is no doubt Germany did not provide Americans with commensurate care. Some assert, however, that life for American POWS in German camps was immeasurably better than that for Russian POWs.

Idealistic Americans called for continued generosity toward the POWs. Cook includes a portion of a 1944 Collier's magazine editorial as substantiation.

We ought to be humane and generous in this mater because we are Americans, and because we have always believed as a nation in decency, humanity, humaneness and a break for the underdog - which war prisoners certainly are. If we should take to mal-treating war prisoners, we would betray something fine in our national make-up; and the consequences of that betrayal would kick back in our own teeth.

The well-researched and documented tome includes some stories Germans shared of their homeland experiences while husbands and fathers remained behind American barbed wire. It places personal stories in their historical period, reviewing events leading to prison captures and progress of the war over the life of the camp. It also deals with conditions after the war and the long delay many German POWs suffered before being allowed to return to their homes.

With the war's end, soldiers no longer qualified as POWs and found their lives changed. Officers no longer had the option of not working. America reduced food rations. Once most former POWs returned to Europe they found themselves forced to work in Great Britain, France, or elsewhere to help rebuild those war-torn nations for months or years before they were allowed to return home. Life became much less comfortable and pleasant than in their POW days.

In the late 1980s, Alabama Governor Guy Hunt issued a call for communities to make 1989 the year of "Come Home to Alabama." Cook says that in years prior to that call, strangers would appear in Aliceville and inquire around in German accented English, "Vhere is dah camp?"

Aliceville residents took Hunt's call to heart and invited their former "guests" to return to the onceagain sleepy town. With the help and encourage- ment of many in the United States and Germany, an official reunion for POWs, guards, and past and present residents came to fruition. Since that first occasion, others have followed. One Aliceville resident, who spent months in a German POW camp could not bring himself to share in the initial reunion. Eventually, he found the ability to meet with these former enemies.

Beyond the reunions, which have included at least one trip by some Americans to Germany, enthusiasm has grown for other commemorations. Some have lent or given prisoner-produced items they have held; POWs have donated copies of their newspapers; guards have shared of their newspapers; a former local soft-drink bottler donated its old plant; and now Aliceville has its own POW museum.

The United States government officially deactivated Camp Aliceville on Sept. 30, 1945. Governmental agencies or private individuals took possession of the camp buildings. The chimney for the enlisted men's club and a surrounding sidewalk in a small town park are all that most can find of this once amazing experiment.

One can find, at the museum, a small gingko tree planted by five former POWs. One who had been for years a reconstructed Nazi now prays for peace. He and others planted that tree, the first type to blossom at Hiroshima after the atomic bomb blast there, with the words, "This tree we now plant at this place. Let it be a symbol of hope for a peaceful future."

In her foreword, Cook reveals she spent time as a late teen as an exchange student in Germany. She found tremendous support there for America at the time. She recalls the tears Germans shed and their tremendous sympathy for America after 9/11. She writes with hope:

In January 2002, with the hunt for Osama bin Laden in full swing in Afghanistan,President Bush announced that captured members of Al Qaeda and the Taliban would not be protected by the Geneva Convention. He based his decision partly on advice from White House Counsel Alberto Gonzalez, who had concluded that these terrorists were not affiliated with a legal government and, therefore should not have rights or be considered military captives.

By that time, I'd read a great deal about the Geneva Convention standards followed with zeal by the United States during most of the World War II. I knew the very positive effects those standards had had on captives held in Camp Aliceville - the respect generated by simple things like hot coffee after a long journey; abundant meat and vegetables; adequate clothing and shelter; recreational, educational and spiritual opportunities - respect ongoing for a lifetime and now being shared with those captives children and grandchildren. I thought about the ginkgo tree former German POWs had planted in front of the Aliceville Museum as an expression of their profound belief in world peace.

The Oneonta Public Library has a copy of Cook's work. Some locals recall experiences they had of German POW out of a satellite camp in Oneonta. Others have spoken of still another camp at Cleveland. While the Aliceville museum has no record of the Cleveland camp, a Birmingham News article written by a Birmingham Southern college student does list the Oneonta site. Cook does explain in her book that the state had, at least, four base camps and 20 satellite ones, with over 17,000 total prisoners.

The review above dwells much on the serious side and with long-range implications. Obviously, any reviewer must limit the scope of the summary; rest assured, however, the book does have many lighter moments. Readers will find themselves chuckling at tales of the lax attitudes on the part of guards, soldiers, camp employees, townspeople and the POWs. They will also find poignant stories of the interned, those associated with the interned, and the two killed in reported escape attempts.

The Aliceville POW Museum and Cultural Center displays many items from the camp. Guests may reach the reach the museum from the Aliceville exit off I-59-20 south of Tuscaloosa.

Thursday, November 20, 2008

German POW Meier Now Buried in Chattanooga National Cemetery

After my last blog entry about the German POW who was shot during a supposed escape attempt from Camp Sutton, I received an interesting response from blogger "Camp Sutton," a retired US Army Master Sergeant in North Carolina who grew up next door to the camp and has become interested in researching its history.

Camp Sutton offered the following interesting information:

--Werner Friedrich Meier was originally buried at Camp Butner, but when that camp closed, his grave was moved to the Chattanooga National Cemetery.

--His grave marker there, as shown above, reads "1Sgt. Air Force" on the first line. The second line reads "German," and the third line lists as date of death, July 11, 1944," which corresponds with the date in newspaper reports for the German POW's death. This grave is located in Section PostC, Site 40-3.

Blogger Camp Sutton also shared the contents of a newspaper article that appeared in The Monroe Enquirer on July 13, 1944:

GERMAN PRISONER SHOT WHILE TRYING TO ESCAPE:

Former Luftwaffe Sergeant Killed By Camp Sutton Guards

A former Luftwaffe sergeant from the prisoner fo war compound at Camp Sutton was shot and killed by guards Tuesday morning during an attempted escape near Van Wyck, S.C.

He was Warner (sic) Friedrich Meier, a member of a group of Germans who have been working regularly in local woodpulp mills on government contracts made in accordance with Geneva convention regulations.

Two guard-escort soldiers of the group detailed as custodians of the working war-prisoners intercepted him in his attempted break and called upon to halt. After hesitating briefly, he continued his flight and they opened fir killing him at once.

Sunday, October 26, 2008

Carolina Newspaper Columnist Questions "Escape" Shooting of German POW

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

THICKET Magazine Features Aliceville POWs

The October/November issue of the new THICKET magazine has a story on page 75 entitled "Behind Enemy Lines." Based on my friend Stacey Torch's visit to the Spring 2007 reunion of former POWs, their guards, and members of the Aliceville community, the article includes interviews with Hermann Blumhardt, who was captured in North Africa in 1943, and Thomas Sweet, who served as a guard at Camp Aliceville during World War II.

The October/November issue of the new THICKET magazine has a story on page 75 entitled "Behind Enemy Lines." Based on my friend Stacey Torch's visit to the Spring 2007 reunion of former POWs, their guards, and members of the Aliceville community, the article includes interviews with Hermann Blumhardt, who was captured in North Africa in 1943, and Thomas Sweet, who served as a guard at Camp Aliceville during World War II.Thursday, October 16, 2008

Encyclopedia of Alabama Is Excellent Resource

At left is a photo of German prisoners of War arriving in Aliceville, Alabama in June 1943, after their capture in North Africa. The photo, which appears in the article titled "WWII POW Camps in Alabama," is from the collection of the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

At left is a photo of German prisoners of War arriving in Aliceville, Alabama in June 1943, after their capture in North Africa. The photo, which appears in the article titled "WWII POW Camps in Alabama," is from the collection of the Alabama Department of Archives and History.I am so pleased that the newly launched online Encyclopedia of Alabama lists my book, Guests Behind the Barbed Wire, as one of the references for its excellent article on the four major camps and the many satellite labor camps that housed German POWs in Alabama during World War II. The article offers an interesting overview for anyone interested in this subject.

I was fortunate to attend the recent Alabama Humanities Foundation luncheon that signaled the launching of this wonderful online resource. Held at the Wynfrey Hotel in Hoover, it was attended by educators and humanities-oriented members of the community as well as Governor Bob Riley and Senator Richard Shelby. Alabama author and historian Wayne Flynt deserves tremendous credit for shepherding this project to completion. The effort was monumental, and so are the results.

Be sure to visit http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/ soon to explore the wide range of information about Alabama--its history, its culture, its industry, and many other facets. A good place to begin your exploration is with Wayne Flynt's excellent essay on the heritage of the state--especially if you don't know a great deal about Alabama. The site is colorful, easy to navigate, and loaded with useful information.

I've added the Encyclopedia of Alabama to my Linked list over to the right, so you can click to it any time you visit my blog.

Thursday, September 18, 2008

Aliceville Museum Director Visits Former German POW in Florida

Thursday, July 3, 2008

An Irony of Place

Mr. Parker has now passed away, but the land where he farmed cotton will now become part of the new prison complex being built in Aliceville.

Thursday, June 5, 2008

A Recent Visit to Aliceville

Back in May, when friends visited from California, they asked if we would take them down to visit Aliceville. Having read Guests Behind the Barbed Wire, they wanted to visit the museum and explore the town where the story took place.

Back in May, when friends visited from California, they asked if we would take them down to visit Aliceville. Having read Guests Behind the Barbed Wire, they wanted to visit the museum and explore the town where the story took place.Chapter One Nineteen Book Club Reads North Across the River

1. Were you aware, before reading this book, that civilians in the South had been deported by Union troops for supporting the Confederacy with their labor?

2. If you had been Synthia Catherine Stewart Boyd, making a phonograph recording for her grandson in the 1940s, what would you have wanted him to remember most about the tale of your experiences during the Civil War?

3. Why do you think the Kendley brothers and sisters chose to remain in Indiana rather than returning to Georgia after the war?

4. What do you think is the significance of the sub-title, “A Civil War Trail of Tears”?

5. Based on this book, how would you compare and contrast the lives of the textile mill workers at that time with those of the antebellum mansion owners we normally think of in connection with pre-Civil War Southern towns?

6. Although this book is non-fiction, dialogue has been created in some places, based on tales handed down in the families of the descendants. Do you think this contributed to or detracted from the narrative?

Guests Wins Bronze Medal in History!

On May 23, Independent Publishers announced the winners in their Outstanding Book Awards competition, and Guests Behind the Barbed Wire received a bronze medal in the History category. The awards were announced at BookExpo in Los Angeles last week.

If you'd like to visit the Independent Publishers website and see the entire list of books (a great summer reading list!), here is the link: http://www.independentpublisher.com/article.php?page=1231

My thanks to all out there who helped make this book possible.

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Book Award News About GUESTS BEHIND THE BARBED WIRE

Monday, May 5, 2008

"The rest of that story right in front of me"

Ever since North Across the River was published, it has been gratifying to learn from time to time how the book helped one family or another piece together "the rest of that story" about a family member who was deported by Yankees during the Civil War. Often, family stories have been handed down, but not a complete picture.

Ever since North Across the River was published, it has been gratifying to learn from time to time how the book helped one family or another piece together "the rest of that story" about a family member who was deported by Yankees during the Civil War. Often, family stories have been handed down, but not a complete picture.Back in April, I pulled an envelope from my post office box with a postmark from Bellmead, Texas. Inside was a wonderful letter from the great granddaughter of Elizabeth Sauls Scoggins, who is pictured here with her husband James in 1895. The picture may have been taken in Rome, Georgia.

"When just a little girl," the letter began, "I would listen for hours as my daddy would tell me stories of when he was a little boy. One such story was about his grandmother who had been kidnapped by the Yankees and taken up North. She would have been about twelve years old at that time. All my life these words haunted me. Why would they kidnap a little bitty thing like her who could have hardly been a threat to the huge Northern army? This simply did not make sense to me."

Kd Wade did some research and found that her great grandmother, Elizabeth Sauls, was one of six children born to Elizabeth Sewell and William Sauls of Jackson County, Georgia. When difficult times came and the family could not stay together, the children were sent to Marietta to live with various relatives. Ellizabeth lived with a family named Sorrell in Marietta. In 1869 she married James Scoggins (Scroggins), the son of a Marietta carpenter. The Scoggins family migrated to Texas in 1895.

Kd Wade learned that, after the chaos of the Civil War, Elizabeth had no idea what had happened to her siblings. Eventually, through a chance meeting with a doctor who had visited Atlanta, she was reunited with at least one of her brothers before her death in 1933.

Still, none of this information answered the question about the Yankee kidnapping story. Kd Wade traveled to Marietta, Georgia in 1999 to see what she could find out. At the Marietta Museum, no one could shed light on the Sauls family and what had happened to them.

"During our seemingly pointless conversation," Kd Wade wrote in her letter to me, "my eyes kept wandering back to a book displayed on the counter, North Across the River. At some point, I remember stopping abruptly in my questioning as the rest of the title hit home. 'A Civil War Trail of Tears.' As I began to leaf through, I could not believe what I held in my hands. Not only was I standing in the very spot that Granny had been taken by railcar to Louisville, but I had the rest of that story right in front of me. I could not put the book down the whole trip back to Texas."

Kd Wade noted that the story of Synthia Catherine Stewart Boyd, told in North Across the River, could easily have been the story of Elizabeth Sauls, too.

The letter ended with the information that Kd Wade's mother is 95 and loves history. The two of them are reading the book again and wanted me to know how much it has meant to them.

"Thank you for uncovering the information and making it available," Kd wrote. "I have no doubt that Divine Providence needed this story told."

I hope Kd Wade knows how much her letter has meant to me!

Wednesday, April 23, 2008

Cousin of Herbert Jogerst gets in touch.

On Saturday, April 12, I received an e-mail from Bruce and Nyla Jogerst. Bruce is a second cousin once removed to Herbert Jogerst, the German POW sculptor I profiled in an earlier post. (See "Herbert Jogerts POW Sculptor" posted on October 2, 2007.)

On Saturday, April 12, I received an e-mail from Bruce and Nyla Jogerst. Bruce is a second cousin once removed to Herbert Jogerst, the German POW sculptor I profiled in an earlier post. (See "Herbert Jogerts POW Sculptor" posted on October 2, 2007.) The Jogersts requested a copy of the materials I have about Herbert Jogerst. They are making a trip from Florida to Illinois and would like to see the Christ of the Ohio statue on Fulton Hill in Troy, Indiana, during their journey.

The package of clippings and the translation of the interview went into the mail today. I hope they enjoy their trip.

The photo above shows Herbert Jogerst's son Elmar with the Christ of the Ohio statue created by his father, German POW Herbert Jogerst. The statue is eleven feet tall and weighs 62,000 pounds. It overlooks the Ohio River.

Thursday, February 28, 2008

Descendant of Roswell mill worker Lydia Swords seeks information

Lydia Swords is believed to have worked in the Roswell mill. There were four or five sisters together, and there is evidence to suggest they may have been part of the deportation to the North in the summer of 1864.

If anyone has information about these sisters, please respond to my blog, and I will share the information.

Thursday, January 24, 2008

Great Granddaughter Shares Memories of Synthia Catherine Stewart Boyd

Synthia Catherine Stewart was nine years old when General William Tecumseh Sherman's troops marched into Georgia in 1864. Her father was off fighting with the Campbell Salt Springs Guards for the Confederacy http://walterstewart.org. She and her mother, her uncle, two sisters and a brother were among those who watched as Sherman's troops burned the New Manchester mill on the banks of Sweetwater Creek outside Atlanta http://www.friendsofsweetwatercreek.org. The six family members were then taken by wagon to Marietta where they boarded a train and made the trip north to Louisville, having been charged with treason for supporting the Confederacy. Synthia Catherine's story, and that of other mill workers at New Manchester and also at Roswell, Georgia, is told in the book North Across the River.

Synthia Catherine's great granddaughter Glenda Hilliard, who makes her home in Abilene, Texas, has shared wonderful memories of growing up with a great grandmother who survived that Civil War trip and then made a life for herself and her family in Texas.

Here, in her words, are some of those memories:

- Synthia Catherine and her family moved to Sidney, Texas, in 1903 when their youngest child (Glenda's grandmother) was seven years old They reared nine children of their own and six younger siblings after her husband's parents passed away. She was a wonderful grandmother and the heart of our family. She was loved by many and known as Granny Boyd by all in our small community.

- I will never forget the gatherings at her house where there was always lots of good food, love, laughter and many stories told. Her house was old and unpainted, without electricity, indoor plumbing, or running water, but we all thought it was a mansion because Granny lived there. It had a big front porch that held cane-bottomed chairs and rockers. There was a metal bucket on a small table with water and a dipper to drink from. We all drank from the same dipper and probably shared more than stories.

- Granny lived with her daughter, Rommie, and son-in-law in her latter years. He sold eggs and butter to the little grocery store in our town. They never had much money but were very frugal and always took good care of the things they had and never wasted a thing. Even their outdoor toilet smelled good. They kept ashes from the fireplace in a big bucket in the toilet to cover the "deposits" we made.

- Granny did all their cooking on a wood stove, and everything tasted like it was cooked by a famous chef. She always sent a surprise to me on Saturdays when her son-in-law came to Sidney to bring eggs and butter to the store to sell. It would be a pretty, handmade dress for my doll, pretty rocks or arrowheads, ostrich feathers, tea cakes that she had made on her wood-burning stove or anything she thought I might like. Then I would send her a surprise when he went home. I usually sent her a jar of maraschino cherries--her favorite--or some beautiful piece of artwork I had done.

- Granny had a great love for nature and all the beauty of God's creation. she often called me (on our crank telephone) to go outside to see a pretty cloud formation, an airplane (which was a rare occasion), or a ring around the moon.

- Granny died when I was eleven, and I thought I would surely die, too. She was such an example, and I feel sure I am a better person today because of her influence in my life. Everyone should have a great grandmother like Granny. All of the grandchildren thought that they were her favorite, but I knew that I was.

Synthia Catherine Stewart http://tattlingtales.com/Study-Guides/New-Manchester-Girl-Study-Guide.html lived to be 96 years old. She is buried in the Sidney Pendergrass Cemetery next to her husband.

NORTH ACROSS THE RIVER Question Finally Answered

Glenda Hilliard wrote on January 24, 2008 to point out that her grandmother, the youngest child of Synthia Catherine Stewart Boyd, is the young woman in the lower left of the photo shown here. She also said, "I love your blog about Granny. She would be amazed that people are still remembering her after all these years...Thanks so much for making Granny's memories come to life."

Glenda Hilliard wrote on January 24, 2008 to point out that her grandmother, the youngest child of Synthia Catherine Stewart Boyd, is the young woman in the lower left of the photo shown here. She also said, "I love your blog about Granny. She would be amazed that people are still remembering her after all these years...Thanks so much for making Granny's memories come to life."When I wrote the book North Across the River (Crane Hill 1999), I interviewed many descendants of mill workers from Roswell and Sweetwater Creek, Georgia, but I was never able to connect with the family of Synthia Catherine Stewart Boyd. In the archives of the Atlanta History Museum, I had discovered the transcript of a phonograph recording she made in the 1940s for her grandson Elwood Boyd--way out in Comanche County, Texas. That recording provided details I would not have had about the mill workers who were arrested by General Sherman in 1864, charged with treason, and sent north so they could not continue to make cloth for the Confederacy. Synthia Catherine was about nine years old when she and her mother and uncle, her two sisters and one brother were forced to make the journey to Louisville, Kentucky.

I checked records in Georgia and in Texas but was not looking in the correct places. I tried to reach a branch of the family in Columbia, South Carolina, but found only disconnected telephone numbers. The Internet was up and running at that time, but search engines were not as efficient as they are now. One red herring in my search was the fact that a reporter for an Atlanta newspaper who claimed to have visited the Boyds in Texas insisted that Synthia Catherine's father had worked for the mill in Roswell, and she would not share her sources.

As I worked on the book and researched facts from the Synthia Catherine transcript and other material, I came to the conclusion that I was as close to positive as I could be without proof that Walter Washington Stewart had been a bossman at the mill in Sweetwater Creek rather than Roswell. I told my publisher the situation, and fortunately, she encouraged me to go with my instinct and write the story as it appeared to me to be true. When the book was published, I kept hoping for contact with the Stewart family.

Time went by. I heard from a number of people with ties to the mill worker story but not from anyone connected to the Stewarts. I attended a reunion at Sweetwater Creek State Park and met members of other families but no Stewarts. Then I became involved in writing the manuscript that became Guests Behind the Barbed Wire and let the question ride.

Last July, to my complete surprise, I received a letter from Glenda Hilliard in Abilene, Texas. "I learned yesterday," she wrote, "about a book you have written about my great grandmother, Synthia Stewart Boyd." The words jumped from the page after so many years, and they were followed by wonderful memories Glenda has of her great grandmother. "She lived in Sidney, Texas, after her family moved from Alabama," Glenda wrote. "That is where I grew up, and so I spent lots of time with her. I remember the day that she made recordings of her memories of the Civil War. Our whole family had gathered at her unpainted house....The records were later transferred to CDs, and roosters can clearly be heard crowing in the background."

Since then, I have learned from Glenda that, indeed, Walter Washington Stewart had been a bossman at the New Manchester mill on the banks of Sweetwater Creek. She has also shared more memories of Synthia Catherine's adult life in Texas, which I will share with you in the next blog installment.